Portfolio

Llanos with Lisa Davenport

Lisa and team are tagging water birds and want to test for bird flu

moreStrangt of Cacti

I’m really happy to announce that our story about the Saguaro Cactus in El Pinacate, Mexico, is out in National Geographic Magazine. We had so much fun shooting this story in the desert with @victor_ammann @batmanmedellin.

Cacti are keystone species in desert habitats providing food and shelter to a wealth of animals. Bats, hummingbirds, butterflies, bees and moths all visit cactus flowers to drink nectar and disperse the flower’s pollen. Pollination is crucial for plants, especially in the desert where pollinators are few and far between. These cacti bloom with large, fragrant flowers that attract the rare visitors they need to thrive.

But did you know that humans too have used cacti for thousands of years for food, building materials and even hallucinogens? However, our relationship with cacti has shifted and today many cacti are critically endangered due to unsustainable collection, habitat loss and climate change.

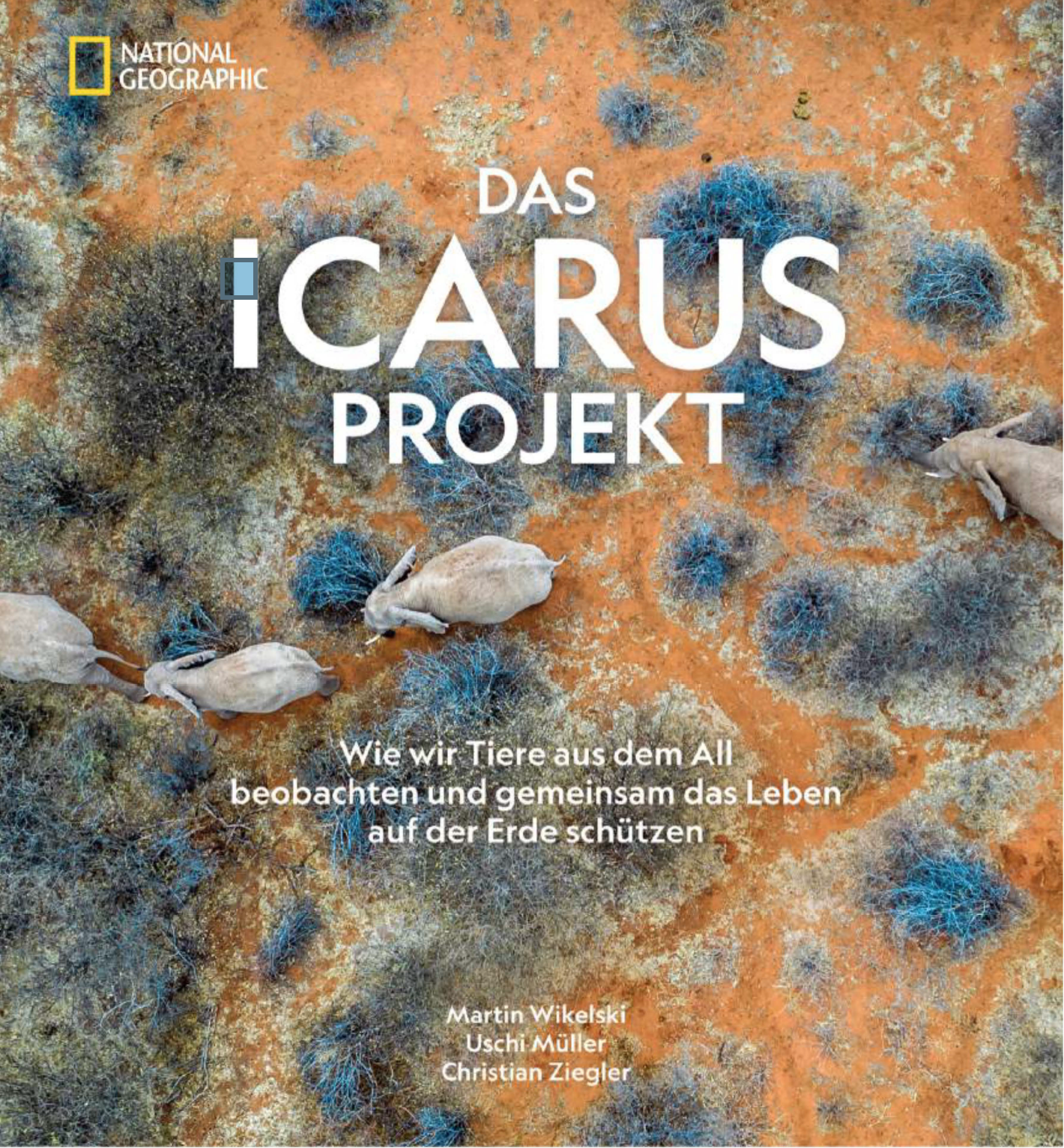

moreICARUS

Book written by Martin Wikelski, Uschi Müller with pictures by Christian Ziegler. Milliarden von Tieren ziehen täglich über unseren Planeten. Ihre Zugrouten sind noch immer ein Rätsel. Durch Mikrosender und Satellitenbachtung aus dem All ist es erstmals möglich, tausenden Tieren gleichzeitig in jeden Winkel der Erde zu folgen. Denn: Tiere warnen uns vor Katastrophen, sagen Pandemien vorher und machen den Klimawandel sichtbar. Ein faszinierender Bildband über ein bahnbrechendes , bei dem es um nichts weniger geht, als um eine bessere Zukunft für Mensch und Tier.

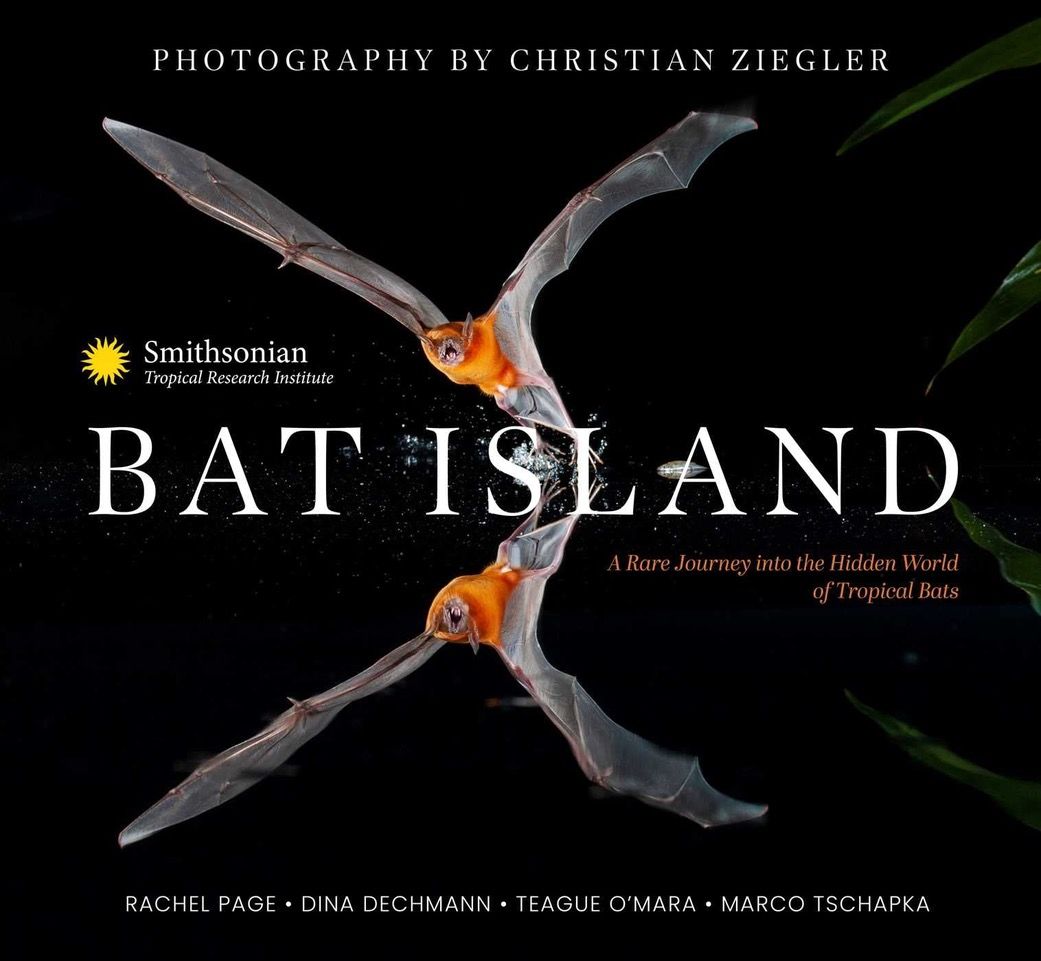

moreBat Island - A Rare Journey into the Hidden World of Tropical Bats

Bats are unique among mammals. They have acquired true flight, provide essential ecosystem services, and represent the ecologically most diverse group of mammals worldwide. Nowhere is this diversity more striking than in the tropics. For decades, scientists at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute have studied the remarkable biodiversity of bats on Barro Colorado Island, a small island in the Panama Canal where an astonishing seventy-six bat species coexist. Stunning photography of National Geographic contributor Christian Ziegler pairs with Smithsonian scientists’ expertise for a captivating visual journey into the world of these elusive night creatures. Synthesizing years of intensive study, Drs. Rachel Page, Dina Dechmann, Teague O’Mara, and Marco Tschapka provide insight into how bats perceive their surroundings, navigate, forage, find safe roosts, and maintain social groups. Alongside award-winning photographs that showcase bats’ diverse ecological adaptations and rich natural history, Bat Island communicates the initiatives needed to ensure the survival of these extraordinary animals, which are critical to maintaining healthy, balanced ecosystems.

moreBiodiversity worldwide

Selections of fruits, animals, food items

more100 years of Barro Colorado Island

Written by STRI

"For the past 100 years, lessons from Barro Colorado played a critical role in the preservation of tropical nature. Barro Colorado Island was formed when the Chagres River valley was flooded to create Gatun Lake, the main channel of the Panama Canal. By monitoring bird populations on the island, scientists realized that when a forest becomes an island (or a forest fragment), it begins to lose bird species, especially during climate extremes. Their work led conservationists to create important connections between protected areas so that wildlife can move from one forest to another in times of need.

Tropical forest research on Barro Colorado Island led to a series of forest study sites in 28 countries around the world (ForestGEO) and to techniques used today to understand how forests protect biodiversity and store carbon, pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere that would otherwise contribute to global warming and climate change.

Work on Barro Colorado also led STRI to establish the Agua Salud experiment in the Panama Canal watershed—the largest tropical reforestation experiment of its kind—providing land use managers with information about how native tree species can be planted to improve water management and avoid flooding, store carbon, and conserve biodiversity to create a sustainable future.

moreBonobo in the wild 21/22

There are not many places in the world where you can photograph wild bonobos - our closest living relative. Bonobos live only in the dense tropical forests south of the Congo River in Central Africa, and to the north of the Congo river - separated by this enormous flat, brown expanse of water - live their cousins, the chimpanzees. Bonobos are shy, secretive and incredibly agile in their forest homes, so that it is almost impossible to photograph in the wild, but at Lui Kotale research camp deep in Salonga National Park it is possible. German researchers, Barbara Fruth and her husband Gottfried Hohmann, have been studying wild bonobos for almost 30-years, and 16 years at Lui Kotale. Bonobos here are now more or less used to these strange humans that follow them noting every detail of their behavior - what they eat, how they interact and communicate, where they sleep. In September and October 2021, I spent six weeks following bonobos at Lui Kotale, getting a glimpse of their secret lives. At moments they seemed almost human; the familiarity of their hands or a certain curiosity in their eyes. At other times I felt like an onlooker into their peaceful world, embarrassed by my species, our history and, potentially, our inability to save them in the wild. Bonobos are endangered and protected by law but their numbers continue to drop as they are hunted for bush meat and the wildlife trade, and their habitat is lost. Perhaps just 15,000 of these beautiful animals remain in the wild. But our closest living relative lives here, and only here - south of the Congo River. If bonobos do not survive here, they will not survive anywhere.

moreGlobal Lianas

Climbing plants belong to one the most diverse and yet understudied group of plants on Earth. There are thousands of species of climbing plants that belong to hundreds of different plant families. Climbers can be found in tropical and temperate forests around the world; the vast majority of climbers, however, are found in the tropics. In fact, the abundance of lianas is a key difference between temperate and tropical forests.

The ecology of climbing plants captured the attention of the early explorer-scientists over the past two centuries. Even Darwin was fascinated by this diverse group plants, and in 1865 he wrote what perhaps became his second most famous book: “On the movements and habits of climbing plants”. Darwin (and others) recognized the unique strategy of climbing plants; these plants avoid building a large trunk, but instead use the trunks of neighboring trees to reach the forest canopy. This strategy allows climbing plants to invest more energy toward acquiring resources and reproducing rather than towards building a bulky trunk. Once in the forest canopy, climbing plants produce prodigious amounts of leaves and flowers, often smothering their host tree.

moreBORNEO – Mast fruiting – a forest in fruit

While many animals eat fruit and disperse the seeds in their feces, others feed on the seeds themselves. Rodents and wild pigs, in particular, love to feast on palm nuts and the large seeds of some canopy trees. However, in Southeast Asia the forests have evolved a strategy to enable some seeds to escape. Here, the trees produce no seeds for years, deliberately starving the seed predators. Then, in a single year, hundreds of forest tree species simultaneously produce huge crops of fruits, satiating the seed eaters so that some seeds survive to grow into seedlings and eventually adult palms or trees. These fruiting events are called “mastings” and typical occur only every 7-10 years in association with rare climatic triggers, such as severe drought or low night-time temperatures.

Recent reports from Borneo, including reliable sources at Danum Valley Conservation Area and the Sepilok Forest Reserve have conveyed that a general flowering is underway, and a mast fruiting event will follow in the period September to November 2019, that is predicted to be the largest in decades. The last mast fruiting event in Sabah, Malaysia, took place in 2010, but the rarity and episodic nature of tree reproduction in Southeast Asian forests makes it very difficult to plan field expeditions to photograph this natural phenomenon. I aim

moreGlobal Fig trees

Fig trees - some 1000 species of the genus Ficus - inhabit tropical and subtropical woodlands and forests around the world. No other tree group has such a distribution (5 continents) and such fruit abundance. Ranging in appearance from little bushes to giant trees, they all share a complex, and highly specialized mode of pollination: each species of fig depends on its own specific species of tiny fig wasp as pollinator. Each species also has a number of parasitic wasps, which use the fig as food without offering pollination in exchange, and there are even parasitoid wasps whose larvae develop inside the larvae of the pollinators.

Tropical figs are unusual in that individuals of the same species flower and fruit at different times, so even during the leanest times there is usually a fig tree fruiting somewhere in the forest. A fruiting fig can pull in hundreds of monkeys, birds, and bats from the surrounding forest, keeping the animals fed even through the hungry months of the late wet season. It’s difficult to overemphasize the role that figs play in tropical forests: without them the lean times would be even leaner.

Each species of fig draws in the fruit-eating mammals and birds of their respective habitats. A fig in the new world tropics will attract a wide selection of monkeys, opossums, squirrels, toucans and parakeets. Meanwhile figs on Borneo might be visited by orangutans, leaf monkeys, hornbills and fruit pigeons during the day and flying foxes and civets at night. In each location will have also their own unique set of visitors.

moreJungle Spirits: A new book

National Geographic photographer Christian Ziegler and tropical ecologist Dr. Daisy Dent take us on a fascinating journey through tropical rainforests around the world. Together they share their love of tropical forests and the story behind Christian’s motivation for becoming a conservation photographer.

With their photography and compelling stories, Christian and Daisy want to excite you about the wonders of the natural world and highlight the urgent need for effective conservation.

moreSecondary Forest in Panama - a hopefully story !

Secondary forests now make up more than 50% of the world’s remaining tropical forests. These forests regrow on abandoned land across the tropics, and could help compensate for the loss of primary forest. Many people assume that when a tropical forest is cut down it can never regrow and develop the same complexity, but evidence suggests that within just 50 years the biodiversity of plant and animal species in secondary forests is on average 80% of that of primary tropical forest. And secondary forests are even more valuable for carbon uptake, these forests grow quickly binding carbon into woody tissue at 11 times the rate of primary forests. Here you can see images from a range of secondary forests in Panama, illustrating the diversity of these ecosystems and the species interactions that have re-established in regenerating forests. In a era of bleak environmental news, tropical secondary forests provide a point of hope.

moreCoiba island - a jewel of biodiversity in Panama

Coiba Island is Central America’s largest uninhabited island (some 500 square kilometers); a truly unique place with many endemic and rare species of animals and plants. Coiba was a penal colony for almost 100 years until 10 years ago, and so through a quirk in history, it is still covered with lush rainforest that has long gone on the mainland - a time capsule with high conservation value. A forested rock in the rich Pacific Ocean that offers a living example of the rich habitats that once prevailed throughout this part of the world, but that are now long gone from the mainland.

moreA giant digg- looking for fossils in the Panama Canal

with Carlos Jaramillo

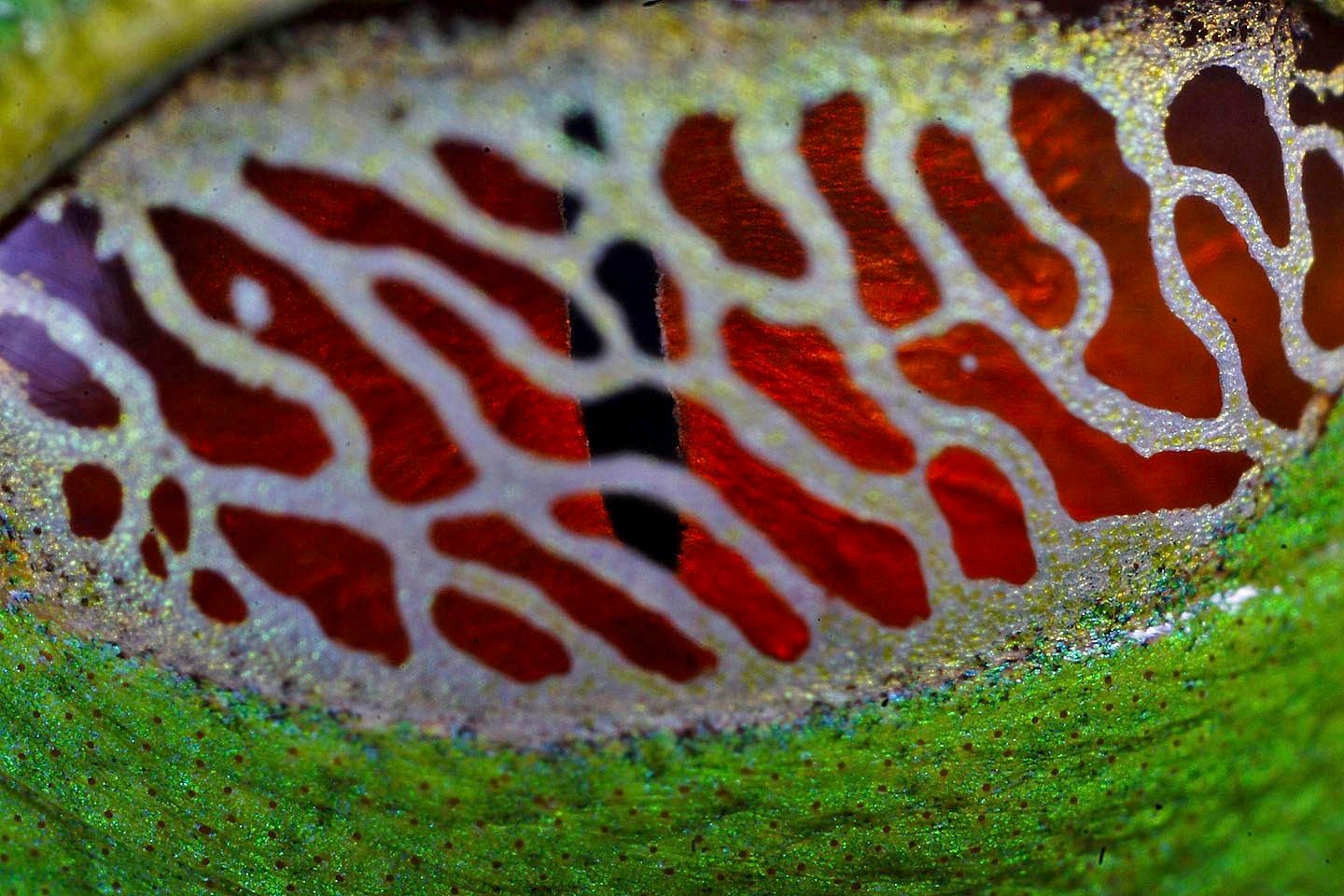

moreThreatened Chameleons of Madagascar

D I S A P P E A R I N G D I V E R S I T Y

Bertrand lifts up the tiny chameleon on the tip of his finger, and we stare at this little marvel in wonder. Early this morning we clambered up over the limestone cliffs behind the beach where we had camped to look for chameleons in the dry forest that covers this tiny island off Madagascar’s north coast. Bertrand Razafimahatratra is my guide and an unparalleled chameleon expert.

He knew exactly where to find these tiny leaf chameleons, carefully searching them out in the leaf litter between the buttress roots of a huge tree about a half-hour hike from the beach. As he stands with one chameleon perched on his finger, he points out another in the dead leaves. I crouch down and gently scoop this microscopic animal onto my palm. I am holding the world’s smallest reptile—Brookesia micra—in my hand. Incredible!

We are on an uninhabited islet just off the coast of Madagascar: a fragment of untouched dry forest in the middle of a clear, turquoise sea. We arrived yesterday in a little motorboat, skimming over gentle waves to land on a perfect half moon of sand where we set up camp while we search for chameleons. Maybe 500 individuals of B. micra live only here on this island—a tiny population of tiny reptiles. Over the last two months, Bertrand and I have driven the length of Madagascar (over 6,000 kilometers, or 3,700 miles) in search of chameleons and we have photographed over 40 of Madagascar’s 76 species.

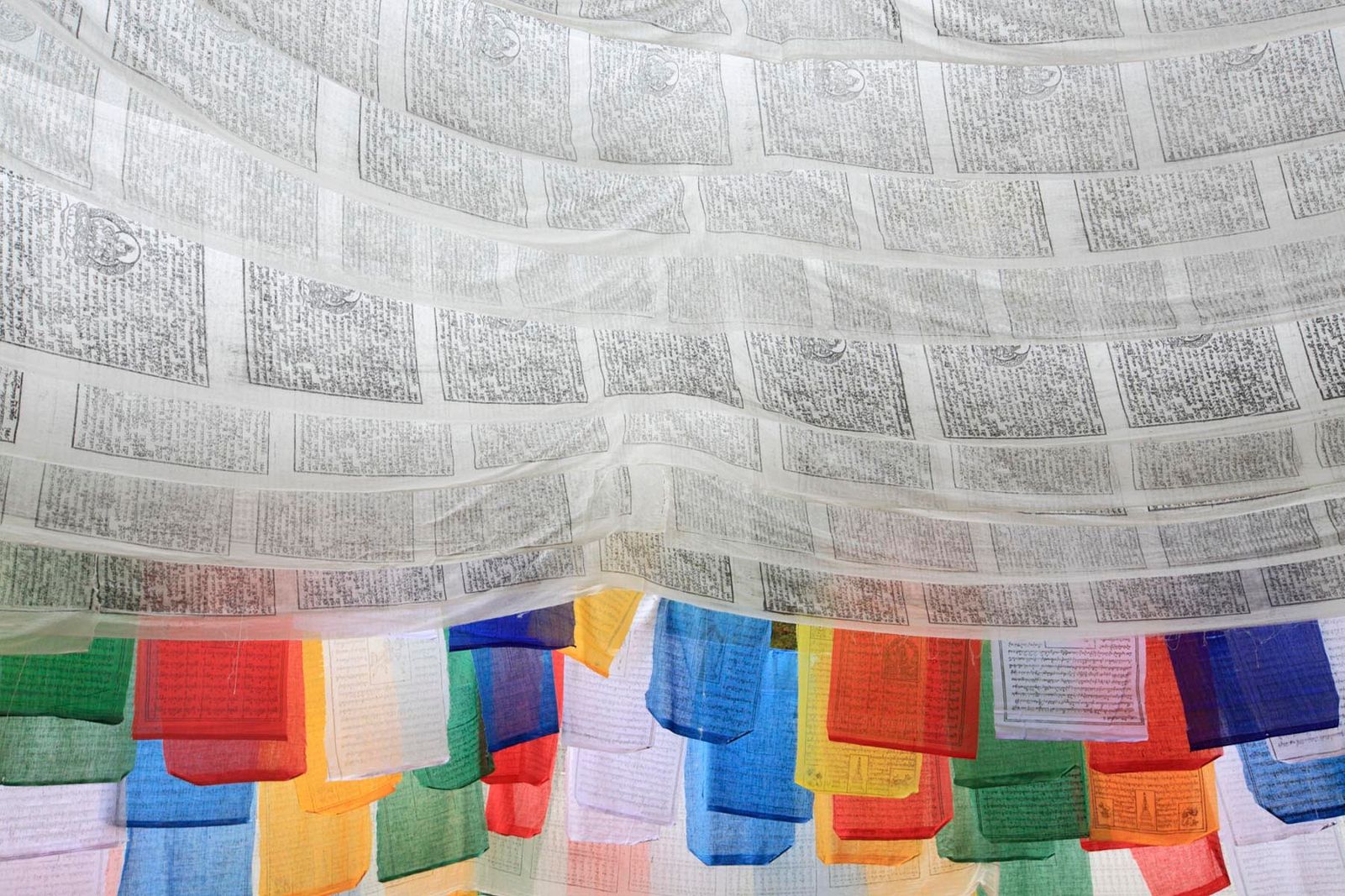

moreBhutan - migration of animals

Bhutan, the mysterious Buddhist kingdom in the heart of the Himalaya, which has been closed off from the world for hundreds of year, spreads across breathtaking landscapes from subtropical lowlands to peaks of more then 7000 meters. With 60% of the country protected by government degree, there is abundant, mostly unaltered, and well protected flora and fauna, a striking difference to all the rest of the Himalaya which has suffered much environmental degradation during the last 150 years. Because of its low population, and low accessibility, Bhutan today is what the Himalayas nature looked like before humans started large-scale damage like logging and hunting. Much of Bhutan’s wildlife is endemic or extremely rare in other parts of the Himalayas. Species like the Takin (Bhutan’s national animal and the origin of the golden fleece), rare primates such as the Golden Langur, 12 species of wild cats including tiger, clouded leopard, and the reclusive marbled cat, as well as a spectacular variety of rare birds, like the Black-necked crane, the stunningly beautiful Monal (a large and extremely colorful pheasant that lives in extreme altitude) and several hornbill species, are among the rarities found here.

more