Threatened Chameleons of Madagascar

D I S A P P E A R I N G D I V E R S I T Y

Bertrand lifts up the tiny chameleon on the tip of his finger, and we stare at this little marvel in wonder. Early this morning we clambered up over the limestone cliffs behind the beach where we had camped to look for chameleons in the dry forest that covers this tiny island off Madagascar’s north coast. Bertrand Razafimahatratra is my guide and an unparalleled chameleon expert.

He knew exactly where to find these tiny leaf chameleons, carefully searching them out in the leaf litter between the buttress roots of a huge tree about a half-hour hike from the beach. As he stands with one chameleon perched on his finger, he points out another in the dead leaves. I crouch down and gently scoop this microscopic animal onto my palm. I am holding the world’s smallest reptile—Brookesia micra—in my hand. Incredible!

We are on an uninhabited islet just off the coast of Madagascar: a fragment of untouched dry forest in the middle of a clear, turquoise sea. We arrived yesterday in a little motorboat, skimming over gentle waves to land on a perfect half moon of sand where we set up camp while we search for chameleons. Maybe 500 individuals of B. micra live only here on this island—a tiny population of tiny reptiles. Over the last two months, Bertrand and I have driven the length of Madagascar (over 6,000 kilometers, or 3,700 miles) in search of chameleons and we have photographed over 40 of Madagascar’s 76 species.

Just like B. micra, almost all chameleon species we have seen are restricted to small patches of habitat, perfectly adapted to their respective environments—from wet rain forests to seasonal dry forests, or highlands to deserts. Take the Labord’s chameleon (Furcifer labordi ), for example, adapted to live in the seasonally dry forests of Madagascar’s east coast. This species spends almost its whole life as an egg. The eggs hatch with the first rains and grow to adulthood, reproduce, and die in the four to six month wet season, leaving the eggs to endure the months of drought. Chameleons are the masters of their chosen habitats.

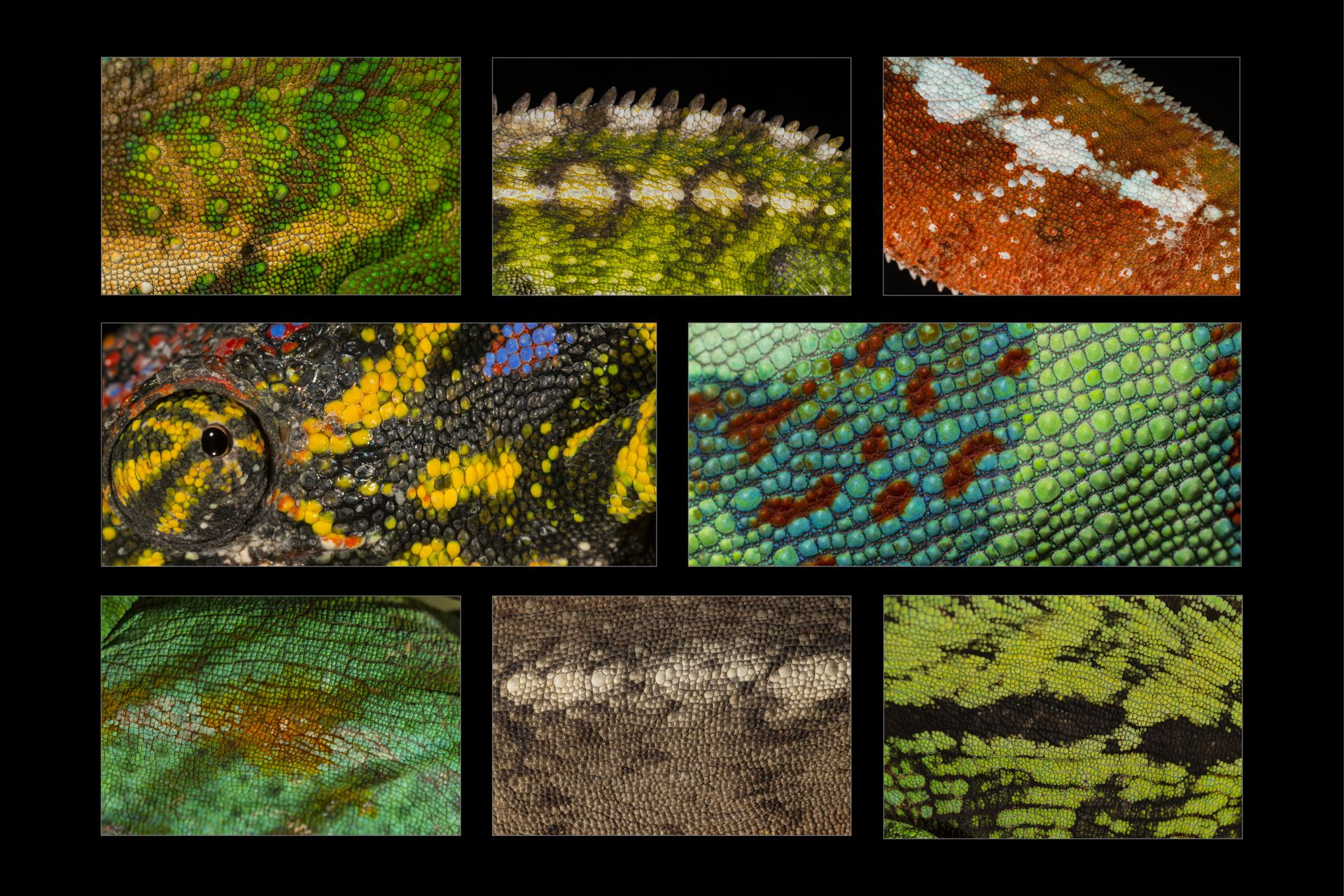

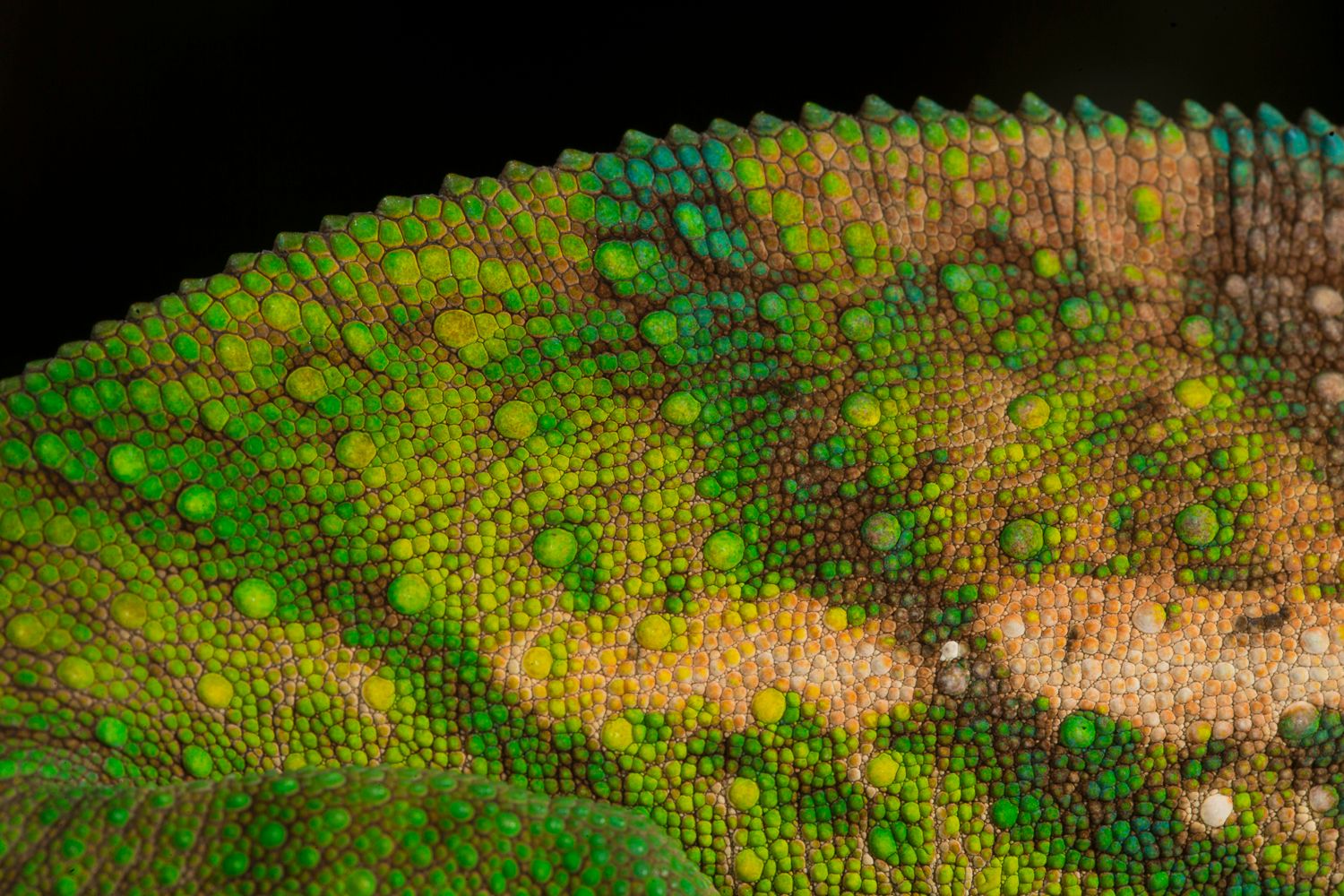

Almost alien in appearance, chameleons have independently moving eyes, they can change the color of their skin on demand, their tails curl into a perfect spiral, and they have odd appendages—an extended knobby nose or a horn protruding from their forehead, and a fantastic extendable tongue for catching insects. Madagascar is the center of chameleon biodiversity; almost half of the world’s chameleon species live here and all are endemic—they live nowhere else on earth. This pattern is seen across all groups of organisms here. Madagascar has more endemic species than almost anywhere else in the world. Alone in the Indian Ocean, Madagascar’s wildlife has evolved in isolation for over 80 million years, generating thousands of species seen nowhere outside this island.

However, as we traveled through Madagascar, we witnessed a landscape worn thin from overuse: deforestation, agriculture, and wildfires have reduced original forest cover to less than 8 percent. Many of the chameleons we have seen live in tiny fragments of habitat. How can these habitat specialists survive without their habitat?

Today, over half of Madagascar’s chameleons are threatened with extinction, and there is a real urgency to act to conserve Madagascar’s remaining natural habitats and their unique species. The dry forest that is home to the tiny B. micra is a reminder of what Madagascar may have looked like a century ago, and, unlike many chameleon species, the world’s smallest reptile is safe in its perfect patch of habitat far from human disturbance.